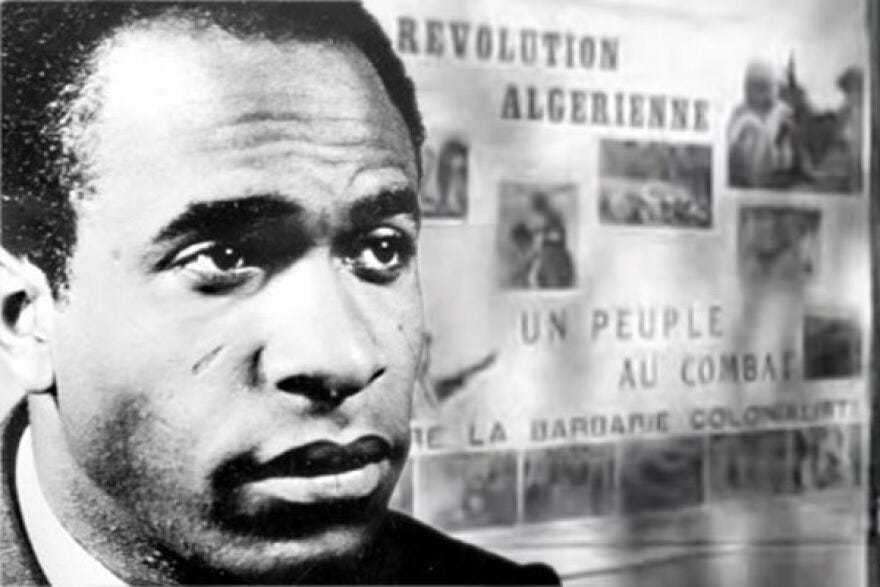

The Revolutionary Thought of Frantz Fanon (Part 2): By Hassan Abdullah Hamdan ("Mahdi Amel")

Révolution Africaine, No. 71 – June 6, 1964 & No.72 – June 13, 1964

Consider becoming a paid subscriber. All funds will be donated to Gaza. Also consider donating to The Sameer Project

Read part 1 for more context of this translated text.

It is upon this inhuman reality of contemporary humanity that Fanon’s penetrating gaze is fixed, whose thought—by its warm and burning outburst—is the profound expression, both poetic and rational, of this reality. Poetic, because, like so many others, subjected to the overwhelming universe of colonial oppression, it was forged in the struggle at the very heart of the epic fight for liberation. It could only be a cry—one of anger but also of hope. Rational, because it was able to extract from the tumultuous and ambiguous movement of daily acts the fundamental lines of history. Putting the event into perspective, it brought the revolution into becoming and from this revealed to us the meaning of the revolutionary future and its orientation. Linking the past to the present in a single intelligible act, it unveiled the possible within the very necessity of its realization. Song, but to better understand and make understood; word, but aimed at action; poetry, but addressed to reason; and reason addressed to the heart—such is Fanon’s thought. To hear it, one must grasp it in its unity. To separate image from concept, rhythm from idea, or cry from meaning is not only to betray it, but above all to betray it in order to disarm it, to stifle in it the revolutionary breath, in short, to silence it.

A Permanent Dialogue

Such attempts have been made by those who feel his words as a bite and who see themselves directly targeted by his threatening condemnations. But such attempts are in vain. For Fanon’s thought, in its articulation and the unfolding of the developmental possibilities inherent in it, practically identifies, as an expression, with the history of the so-called underdeveloped peoples. One cannot mystify a thought with which millions of men maintain, through their social practice, a daily dialogue that enriches it and makes it perpetually alive and current. This is all the more true since those who engage in this practical dialogue with Fanonian thought belong especially to that land of Algeria, which constitutes the space within which this thought moves and develops.

Thus, if it wishes to be constructive and authentic, the gaze aimed at this thought must be one of questioning. But every question is a putting-into-question. Human thought is such that, to consolidate itself in its unity, to respect its continuity, and to remain faithful to itself, it must put itself to the test and risk breaking apart in the very act by which it constitutes and structures itself. This is the adventure of all thought that claims to be universal: if it interrogates itself, it emerges greater and stronger and is founded on and by the critique of its foundation. To embrace the reality from which it arises, thought must submit to its movement and grasp, not the fact, but its becoming; not the isolated act, but its historical meaning.

It is in the light of this kind of understanding that we would like to continue a dialogue that, regrettably, can only be theoretical, but which hopes to find in practice an effective extension—a dialogue with certain aspects of Fanon’s thought, not with its entirety, which exceeds both the scope of this study and the limits of our capacities. But, out of scrupulous fidelity to this thought, we will endeavor to bring to light those aspects which constitute, in an apparent way, not a secondary or peripheral fringe, but the original core and fundamental intention. To do so, the method that seems most adequate to our inquiry is to follow the very movement of the investigative effort of Fanonian thought itself, while linking it, as an indispensable background from which it draws its meaning, to the very movement of the reality on which it bears.

The Beginning of Another History

From its very first impulse, Fanon’s thought places itself at the heart of the colonial problem, defining it in new terms that may scandalize some refined minds. Right from the opening lines of The Wretched of the Earth, a truth—our history’s truth—is pronounced in a staccato and brutal language, proportional to the real violence of the truth it expresses:

Decolonization is always a violent phenomenon… [it] is quite simply the replacing of a certain “species” of men by another “species” of men. Without any period of transition there is a total, complete and absolute substitution. […] that kind of tabula rasa which characterizes at the outset all decolonization. Its unusual importance is that it constitutes, from the very first day, the minimum demands of the colonized. (it is) a program of complete disorder.

Through this, indeed unusual, language, the colonized reason expresses its universe. Pure violence in its presence, the colonial universe betrays its secret in the pure immediacy of its existence; in it, everything is appearance, or more precisely, its entire being becomes appearance. For it is, in its very rationality, constructed such that in order to realize its dialectic, it must necessarily paralyze in its becoming the very dialectic of its becoming. And when its internal evolution reaches its end, everything in it is revealed. It is the halt of history. It is the beginning of another history.

It is therefore not strange that the first moment of Fanonian thought is a descriptive moment—an almost Sartrean phenomenological description—which derives its legitimacy not from this philosophical method, but rather from that privileged moment in the history of the colonial universe where colonial history is negated and where the world tears itself from its foundation to become one with its image, thereby causing all temporal dimension to disappear. Indeed, the colonial universe is, Fanon tells us, a Manichean universe. On one side all evil, on the other all good. On one side the colonizer, on the other the colonized. On one side all the world’s strength, on the other all its humiliation. An insolent structure in its simplicity: the two poles of this colonial universe’s structure absolutely oppose each other in pure exteriority. Or rather, the interiority of the colonial relation is made up of pure exteriority.

The two terms of this false unity exclude each other absolutely. Without mediation, any historical dialectic is impossible. This radical break that occurred within colonial reality thus makes any possibility of a colonial becoming impossible. This absolute blockage of all historical becoming, both individual and collective, is tragically experienced by the colonized at every level of their daily life. Facing the colonizer in the fields, the boss in the factories, their judges in the courts, the gendarme or the horrible and contemptuous legionnaire at every step in the street, the colonized runs, in the smallest details of life, into this closed and suffocating universe, as if against an immense impassable wall. They live their becoming, in their flesh and bones, as a pure impossibility of becoming. They are frozen in a motionless world whose space is plenitude, experienced as oppression.

Finding themselves in total powerlessness to move freely, the colonized dream of action, of leap, of aggression. Unable to truly liberate themselves, they liberate themselves on the plane of the imaginary. But this imaginary liberation only sharpens their real oppression, which at a first moment finds outlet in a displaced outburst of revolt against the brother. This alienated liberation therefore constitutes an imaginary, even magical, destruction of the colonial order, and in fact expresses a genuine collective self-destruction.