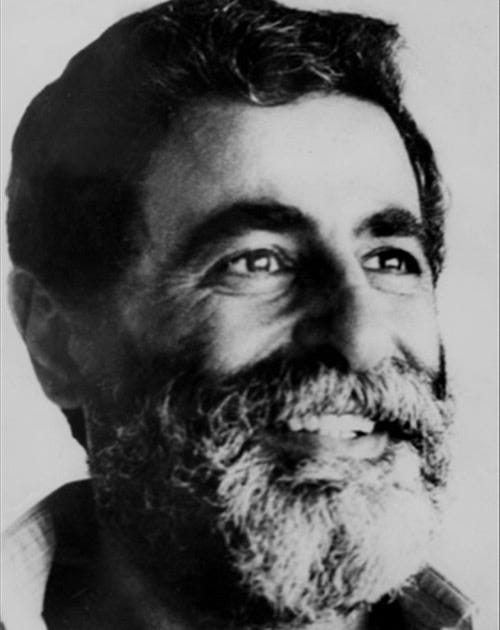

The Revolutionary Thought of Frantz Fanon (Part 1): By Hassan Abdullah Hamdan ("Mahdi Amel")

Révolution Africaine, No. 71 – June 6, 1964 & No.72 – June 13, 1964

Consider becoming a paid subscriber. All funds will be donated to Gaza. Also consider donating to The Sameer Project

In its division of the world into two fundamental categories, men and sub-men, the history of humanity bears the mark of the West. Its movement is precisely that of this duality, which appeared as its ultimate form, especially in the last decades of the 19th century. By whatever name they are called—backward, barbaric, indigenous, or underdeveloped—these sub-men remain, even through their evolution, the by-products of humanity, and their designation as such constitutes the very foundation of the history of the West as the dominant history of humanity. The men made history; the sub-men endured it. This was the reign of the West. The universe was its home. Everything proceeded harmoniously within the framework of this dualistic—but simple—structure of the world.

But the sub-men begin to awaken from their centuries-old slumber, and by claiming their belonging to humanity, they strive to integrate themselves into history, thereby sowing the first seeds of a profound unrest that threatens the harmonious development of the Western order. Yet they awaken into a misery in which they find themselves entrenched and whose cause they grasp—which, for them, lies in that very dualistic structure of the world that opposes the revolting misery of some to the scandalous opulence of others by an antagonistic movement whose foundation is none other than the dominant and colonialist history of the West.

Isolated from its meaning, this misery was ineffective. It constituted no threat, no danger. It was absurd in its nakedness, accepted as fate. But from the moment it found its meaning in the consciousness of the sub-men who lived it, it became a threatening force opposing the dominant history that engendered it. By rejecting it, these sub-men intend to forge their own history. But this rejection, which can necessarily only take the form of violence, is perceived by the colonialist West as a threat to its own domination of history, as a weapon that shakes it to its core. To maintain its domination, it intends to preserve the division it implanted at the heart of the world, at the heart of man. Between it and the others—that is, us— a seemingly unequal struggle unfolds and gives the modern era its historical meaning.

It is upon this inhuman reality of contemporary humanity that Fanon’s penetrating gaze is fixed, whose thought—by its warm and burning outburst—is the profound expression, both poetic and rational, of this reality. Poetic, because, like so many others, subjected to the overwhelming universe of colonial oppression, it was forged in the struggle at the very heart of the epic fight for liberation. It could only be a cry—one of anger but also of hope. Rational, because it was able to extract from the tumultuous and ambiguous movement of daily acts the fundamental lines of history. Putting the event into perspective, it brought the revolution into becoming and from this revealed to us the meaning of the revolutionary future and its orientation. Linking the past to the present in a single intelligible act, it unveiled the possible within the very necessity of its realization. Song, but to better understand and make understood; word, but aimed at action; poetry, but addressed to reason; and reason addressed to the heart—such is Fanon’s thought. To hear it, one must grasp it in its unity. To separate image from concept, rhythm from idea, or cry from meaning is not only to betray it, but above all to betray it in order to disarm it, to stifle in it the revolutionary breath, in short, to silence it.