The Insurgent Fish in Counterinsurgent Waters

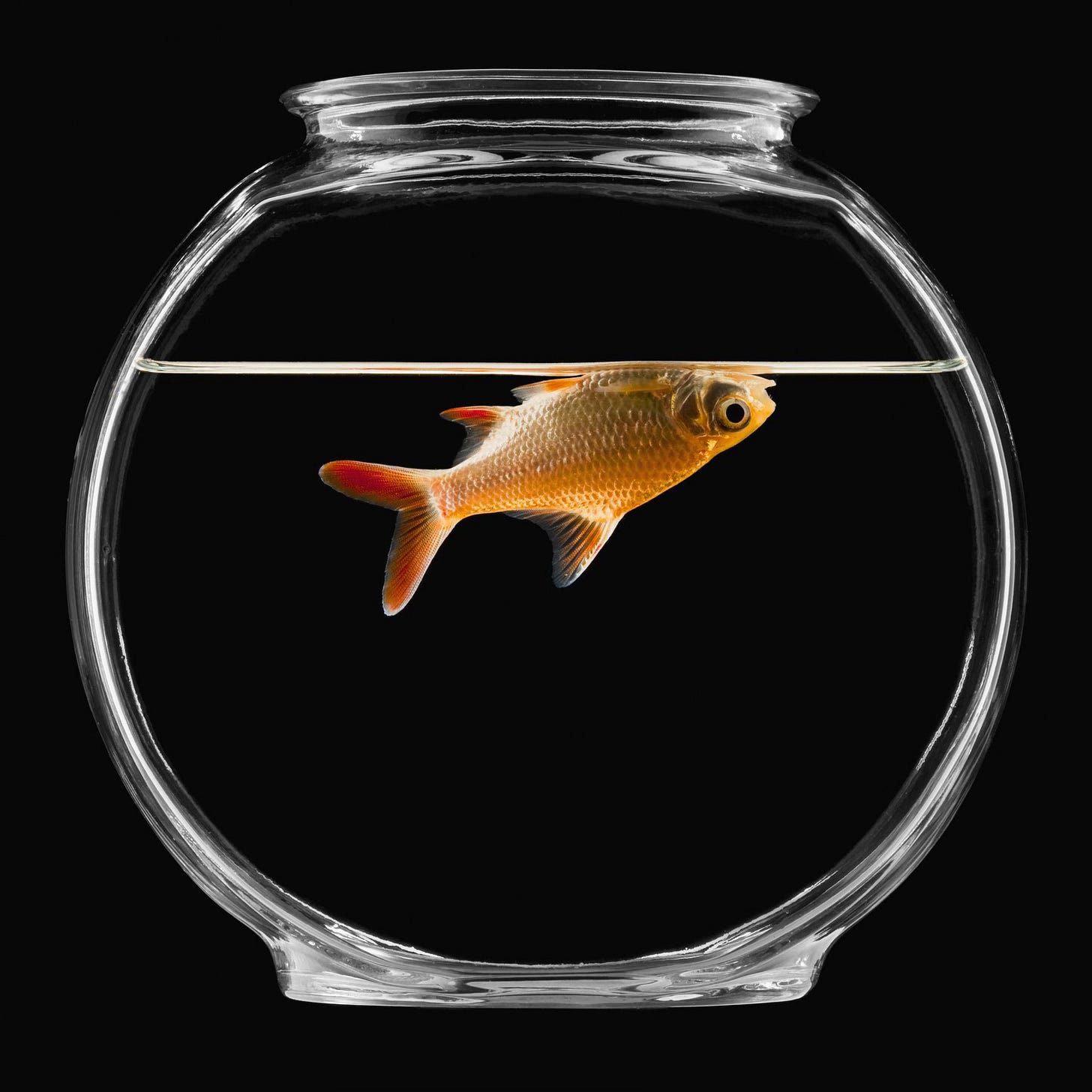

Regaining the allegiance of a community that would otherwise support a subversive and revolutionary movement is central to counterinsurgency. It’s not for nothing that counterinsurgency theory and praxis has used Mao’s fish and water analogy to convey a clear message: an insurgent fish cannot survive for very long if the water in which it thrives has been contaminated by counterinsurgency. If the water, that is, the people, adopt the ideology proposed by counterinsurgency’s propaganda wing, the fish will be unable to proliferate materially or ideologically without the people’s support.

This means that for counterinsurgent operations to gain the support and allegiance of a population will depend on more than ideology. A particular community must see “with their own eyes” some progress once it aligns itself with counterrevolutionary forces. According to Frank Kitson, prosperity is “a potent weapon in the struggle against those who wish to overthrow the existing order, but also there would be little point in defeating the insurgent only to be left with a ruined community” (50-51). The fish and water analogy can therefore be extended to the material reality that creates the conditions for insurgencies to emerge in the first place. The people’s support of revolutionary and counterrevolutionary forces will also depend on how their basic needs are met. While insurgencies will aim to increase the productive forces in defense of the people’s autonomy and self-determination in their protracted anti-colonial, anti-imperial, and anti-capitalist struggle, counterinsurgencies will seek to increase productive forces to defeat an insurgency and to maintain domination and exploitation, even if small concessions have to be made in order to defeat the former.

The State will promise or implement economic reforms to convince the population that change is on its way and that insurrections will only get in the way of development through their “terrorist” activity. The Alliance for Progress is a clear geopolitical and economic policy the US implemented during the Cold War to apparently improve the material conditions, not because of altruistic reasons, but as a strategy against the rising tide of insurrection. Ultimately, the legitimacy of the State and anti-State forces depend on the people who give it strength. Reforms also go hand in hand with ideological warfare as the latter will aim to convince the people that the former will not be successful with the existence of the “barbaric,” “savage,” and “terroristic” activity of an insurgency, while the former will strengthen the latter by providing “proof” that change can happen from within. As Kitson notes, the “people will prefer to back a limited advance offered by the government” for its limited scope than the “far-reaching” revolutionary transformation of an insurrection “because of the greater [perceived] likelihood of getting something” in the present (51).

Reforms are therefore counterinsurgent policies of containment, bandages that prevent structural change and persuade people to side with the State that has historically oppressed them. If reforms seek to minimize and ultimately end the support system of an insurgency, policies must relate to an insurgency’s cause, which has found resonance in a people’s historically specific struggle. If an anticolonial struggle is fighting for complete territorial and political economic autonomy, the colonial government may implement minor agrarian and land reforms to discredit the revolutionary struggle. If a student movement demands the radical transformation of the university and its ties to Israeli weapons manufacturers, university administration may establish committees to implement reforms that will never materialize but will weaken the movement. If living conditions have reached a point where working-class people begin to take subversive direct action, the government may use charismatic “socialist” politicians to drain the energy out of a movement, reducing its demands to reforms that, once again, will not change the economic structure profiting from our disposability—that is, from our wasted lives, labor, and land that generate surplus value for capitalism, particularly extracted from the Global South.

When ideology and reforms do not work or when people militantly aligned with the resistance refuse the compromise the State wants to impose, countersinsurgency initiates a more explicitly violent approach. For example, the British implemented a policy of enclosure by putting hundreds of thousands of Kikuyu in concentration camps, physically separating them from the Mau Mau resistance, for these communities were seen as its economic and military foundation. As Caroline Elkins writes, after conducting hundreds of interviews of survivors, “I’ve come to believe that during the Mau Mau war British forces wielded their authority with a savagery that betrayed a perverse colonial logic: only by detaining nearly the entire Kikuyu population of 1.5 million people and physically and psychologically atomizing its men, women, and children could colonial authority be restored and the civilizing mission reinstated” (xiii). The ethnocidal structure and annihilatory logic of imperialism and colonialism are quickly recalibrated when resistance cannot be “pacified.”

Decades before the Mau Mau rebellion, during the Scramble for Africa, Elkins notes that Francis Hall, who was an officed for the Imperial British East Africa Company, led several raiding campaigns against Kikuyu communities, they resisted from the very beginning. This led him to write his father, a British colonel, suggesting that the “only one way to improving the Wakikuyu…is [to] wipe them out; I should be only too delighted to do so, but we have to depend on them for food supplies” (3). Here we see the contradiction between the ethnocidal structure’s annihilatory logic with the material economic conditions to survive without forced labor. Despite this dependence, Kikuyu villages that continued to resist were systematically destroyed. Similar to the Palestinians in Gaza who have been violently displaced, Kikuyu communities fled to the interior to escape the armed invasion in the late 19th century.

With vast lands now “empty” of Indigenous peoples, settlers were recruited to increase agricultural production. Relevant to point out is that Zionists considered East Africa as a potential region to colonize and settle. British newspapers would go as far as to publish advertisement to persuade “would-be settlers”.

“Settle in Kenya, Britain’s youngest and most attractive colony. Low prices at present for fertile areas. No richer soil in the British Empire. Kenya Colony makes a practical appeal to the intending settler with some capital. Its valuable crops give high yields, due to the high fertility of the soil, adequate rainfall and abundant sunshine. Secure the advantage of native labor to supplement your own effort.”

The dispossession of land and ethnic cleansing of Indigenous people are not unique to British imperialism but reflect the Euromodern colonial policy that could be traced back to the 15th and 16th century. In the 19th century, however, with industrialized means of warfare, imperial counterinsurgent warfare at the time, Elkins argues, was akin to big-game hunting rather than actual combat, no less genocidal than Spanish or Portuguese colonization but certainly more efficient.

As colonization solidified and settlements emerged in Kenya, agricultural production was still a serious problem for white settlers. To resolve this, colonial administration established Indigenous reservations, similar to the Bantustans in South Africa and reservations in the US at the time. The aim was to fragment the social fabric and confine the Kikuyu people into unproductive lands. To increase revenues and force Indigenous people into the wage economy, taxation was implemented so that they would search for work in the fertile settlements, which would allow them to pay their taxes and provide for their families. Another regulation that parallels other settler colonial projects is the control of the Indigenous population’s movement. African workers needed a permit to travel between their reservations and the white settlements, no different from Palestinians. Elkins observes that by 1920, “all African men leaving their reserves were required by law to carry a pass, or kipande, that recorded a person’s name, fingerprint, ethnic group, past employment history, and current employer’s signature” (16). Indigenous peoples placed their permit in a metal box around their neck, which was referred to as a goat’s bell (mbugi). One of the Elkin’s participants, who was forced into the coercive, exploitative wage economy, expressed the following in one of her interviews: “I was no longer a shepherd, but one of the flock, going to work on the white man’s farm with my mbugi around my neck” (16). The dehumanization of colonized people in Africa, once again, parallels other colonized regions, whereby the colonized are portrayed and treated as inferior while the settlers are presented as virtuous pioneers on a civilizing mission to develop wasted lands and savage peoples.

When the Kikuyu resisted these coercive policies of enclosure, taxation, and control of movement by sabotaging settler productive activities and machinery or by continuing to increase their agricultural productive capacities to lessen the need to participate in the settler’s wage economy, the colonial administration implemented another tactic to prevent the Kikuyu from growing profitable crops such as tea and coffee and owning a certain amount of cattle, though they could grow maize freely before the end of World War II, when grains had to be sold at a set price. This forced more of the colonized population to look for work in white settlements. The political economy linked to agricultural production thus subordinated Indigenous labor and products so that white settlers could have an advantage in the market. This illustrates the racial capitalist designs in settler colonies, no different from other regions which had implemented similar policies to contain, tax, control, and limit the production of Indigenous peoples in order to create a state of economic dependency on the white ethnoclass.

In times of insurgent resistance, however, these policies would become more violent and indeed genocidal, which we’ve seen time and again in Palestine, the US, Guatemala, and other colonized communities who tried to reclaim their land and labor. Before entering its more explicitly genocidal phase, some policies sought to delegate power to a co-opted Indigenous class. Colonial-appointed chiefs in Kenya were created to manage and control the Indigenous population, particularly surveil and punish any form of resistance, as well ensure the effective recruitment of labor and taxation. This new political structure played into the colonial trope of tribalism, but in fact it contradicted the governance structure of elder councils within Kikuyu communities that had never been ruled by a chief, let alone one appointed by the colonial government. As in other regions, these colonially appointed leaders would be rewarded for their service. The chiefs who failed to effectively control a population would be quickly stripped of their title and replaced with another.

With this new political structure, we see a clear counterinsurgent policy alongside the emergence of subversive practices and insurrections against an illegitimate authority within Kikuyu communities. The seed of rebellion had been sown at the beginning of colonization, but it began to germinate under the internal colonialist governance and racial capitalist political-economic structure that further fragmented the Kikuyu people, divided between the dispossessed majority, who were heavily exploited and dominated, and an Indigenous minority who benefited from and participated in colonial rule.

Notes on following post:

The governance structure alone is therefore insufficient in stopping a population from rebelling. Power alone must be accompanied by ideological warfare, which in colonial contexts has been dominated by religion and education. Christian missionaries of different denominations competed to save the soles of the “savage” population. They used Indigenous labor to build churches and school that re-educated Indigenous peoples in Western ways of life, which served as the ideological basis for legitimating the political economic structure.

It is this genocidal history that shaped the response to the Mau Mau rebellion.