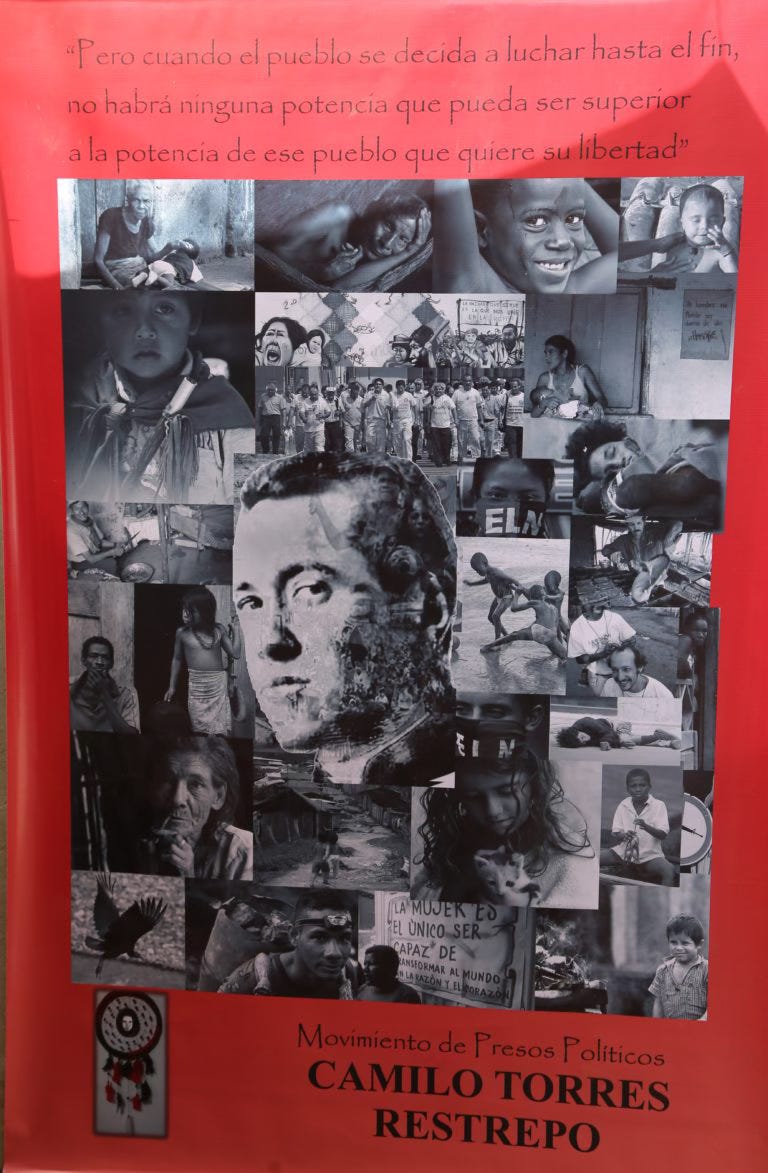

Solidarity with Palestine: Camilo Torres Restrepo Political Prisoners Movement (Part I)

There are peoples who, despite being separated by geographical distances, by their cultures, by their historical developments, and by their languages, are similar and are united by the circumstances that have led them to endure conditions of invasion, conquest, subjugation, and colonization; therefore, this has also led them to identify with one another in their struggles for independence and liberation throughout their existence.

What do the peoples of Palestine and Latin America have in common? Apparently nothing. We are almost at opposite ends of the earth. The deserts in Latin America are relatively small, the forests and jungles are lush, and the waters are abundant, as is the land itself, which stretches from North to South, guaranteeing a variety of climates that very few regions of the world can enjoy.

On the other hand, our languages—though influenced, and not insignificantly, by Semitic and Arabic languages—are quite different from those of the peoples who preceded us in history by creating the first known civilizations in that land which, in the midst of aridity, still flows with milk and honey. Nevertheless, our religions, the result of European invasion and conquest, have their origins in the Mesopotamian peoples, who themselves were invaded—ironically by one of the very peoples they had given rise to, never imagining that it would one day become their executioner.

“We are united by a past of invasions and conquests.”

Thus, a past of invasions and conquests binds our…peoples; for the Palestinians this goes back many centuries, for us a bit less, but with the same vision on the part of the invaders: to wipe out anyone and anything they judge not to align with their ideology, with their political interests, but above all with their economic interests.

Thus, both Palestine and Latin America were invaded and conquered by a caudillo leading a horde that considered itself sent by God to appropriate the riches of the occupied territories. Palestine was conquered by Moses and Latin America by Christopher Columbus. Neither of the two lived to see the land their God had promised them, although both were able to glimpse the wealth these lands contained—wealth that continues to be the motive for wars and plunder.

However, the prize has not been easy for the conquerors and invaders: the native and subjugated peoples have known how to oppose and resist the fate that the metropoles sought to impose. From the beginning, both peoples have sustained a constant struggle, under conditions of inferiority, to restore our independence, freedom, and dignity. The development of that struggle has exposed us to extreme cruelty, given the brutality with which the conquerors have wielded violence to achieve and perpetuate their interests. One consequence is that many of us who committed ourselves to that struggle have had to pay with our physical freedom—the audacity to refuse subjugation and extermination like sheep led to the slaughter without uttering a single bleat.

“Those conditions of inferiority and asymmetry that we speak of have not been only in the military field but above all in the media.”

And the truth is that we have not remained silent, because as Pepe Mujica already said: “no lamb was saved by bleating” (Mujica, J 2016). We have not stayed with just denunciations and complaints; instead, we dared to carry out civil and armed resistance in order to attempt, with dignity, the restoration of the rights that are inherently ours. Of course, the conditions of inferiority and asymmetry we have spoken of have not existed only on the military front but, above all, in the media, used as the main weapon by global hegemonies in modern warfare.

This is how concepts and labels are implanted in global opinion—terms such as terrorist, criminal, delinquent, murderer—to describe popular fighters, whether their means of resistance are their bodies, fists, a stone, a stick, a rifle, a machine gun, a homemade rocket, or, in many cases, simply their voice. Meanwhile, the crimes committed by the powerful states and their satellite allies are framed in global opinion with adjectives of heroism, portrayed as defending peace and the order of law-abiding citizens. Moreover, these official crimes are carried out with machines of death produced in the workshops of large multinational arms corporations. It seems that defending oneself with weapons made by the people or obtained illegally is illegitimate, while using sophisticated, factory-made weaponry renders civilian deaths “collateral damage.”

The same applies to prisoners in the context of conflict: if rebel forces take captives, the states immediately label them as “kidnapped.” Meanwhile, those of us deprived of liberty in official prisons are not even recognized as prisoners of war, much less as political prisoners, except in some expressions from society through individuals who have risked their lives defending human rights—and particularly those of us imprisoned because of conflict, as recognized under International Humanitarian Law.

Even so, the denial of our status cannot erase the reality of political prisoners worldwide, in countries still under colonial influence and oppression by creole elites aligned with imperial interests. Reality is more stubborn than political narratives.

The existence of political prisoners, including prisoners of war, is undeniable, as are the similarities in the treatment imposed by states seeking to subjugate us and use us as examples to discourage ongoing resistance, dreams, hopes, and utopias. These similarities include not only the denial of insurgent status but also isolation, long sentences, prison conditions, and violations of procedural guarantees, the latter being the most common.

It is enough to say that, from what we know of the conditions Palestinian political prisoners face, while similar to ours, theirs are far more degrading. This begins with absurd life sentences, as if the entire Palestinian people were not already condemned—both in the two largest open-air prisons in the world, Gaza and the West Bank, and for those subjected to perpetual exile. Furthermore, they have no right to contact with family or lawyers, nor are they allowed to receive correspondence. A significant number of prisoners are children, whose only “crime” has been being Palestinian or, at most, daring to throw a stone at a war tank.

“For more than 30 years, efforts have been made to find a nonviolent resolution to the armed conflict we have faced for nearly 60 years.”

In that global, Latin American, and particularly Colombian context, efforts have been underway for more than 30 years to find a nonviolent resolution to the armed conflict we have faced for nearly 60 years. Partial agreements have already been reached with several guerrilla organizations, but they have done very little to address the root causes of the conflict. On the contrary, these causes have become increasingly acute, reflected not only in poverty, discrimination, and exclusion, but also in the killings of leaders and members of social and popular organizations, whose only “crime” has been to challenge the political and economic model that insists on exploiting all natural resources for the benefit of multinational capital.

The most recent agreement was signed in November 2016 with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People’s Army (FARC-EP), but it is currently being ignored by the government and Congress, turning this new attempt at peace into yet another frustration—repeating a pattern that dates back to 1782, with the capitulations signed between the then Viceroy and Archbishop Eduardo Caballero y Góngora and the leaders of the Comunero provinces of Socorro, who had risen up against “bad government” but not against the king.

Our history has been shaken by wars and peace efforts, all of which have failed due to the oligarchy, which refuses to give up even a single cent of its fortunes or an ounce of its power. As Jorge Eliécer Gaitán stated before the Congress of the Republic in reference to the infamous Banana Massacre: “Painfully, we know that in this country the government has murderous machine gun fire for Colombians and a trembling knee on the ground before American gold” (Angel, M. 2012).

In this context, the National Liberation Army (ELN) has been attempting since 1991 to establish an open, frank, and sincere dialogue with each successive government, without ever being able to consolidate a true process that could at least open the way for the transformations needed to make armed uprising no longer necessary.

“Since our inception, we have promoted—from the most oppressive of capitalist institutions—the making of national historical memory into a more comprehensive and truthful space.”

In the course of these various efforts, the political prisoners of the ELN have played a leading role since 1992. From Bellavista Prison in Medellín, where we live alongside members of the Camilo Torres Restrepo Political Prisoners Movement (MPPCTR)—which was created during the last term of the Uribe Vélez government (2006–2010) to facilitate dialogue between the executive branch and the ELN guerrilla—we have, since our inception, promoted the idea, even from the most oppressive of capitalist institutions, of making national historical memory a more comprehensive space endowed with truth about what the social and armed conflict in the country has been.

Another pillar of our work focuses on the recognition and dignification of the status of political prisoner. For this task, we consider it important to make our history visible through our own narrative, turning the stories with which we construct our memories into a tool of protection against those who distort history to serve particular interests. For this reason, the emphasis on dignifying our status as political prisoners is part of the effort to erase, from a strategically constructed collective imagination, the neutralized and vilified image of the insurgency.

We have completely transformed the space we inhabit, and what the guards call the “Technical Zone” has become a museum of realities and a hopeful space of responsibilities. Collective work and the pursuit of an organized and organic life are some of the principles that define this project of ongoing action and reflection.

The “Territory of Sowing, Dreams, Knowledge, and Hopes,” as we call it, is a site of “hope in despair,” as written on one of the murals that enlivens the yard. This mural is part of our work and stands as a testament to collective construction as an approach to building alternative realities in collaboration with various social organizations and popular processes. In continuous dialogue with civil society, our collective proposes a network of memory connected to the victims, but above all guided by the pursuit of truth. This takes into account not only our status as political prisoners but also as warriors and citizens involved in the social conflict and committed to the construction of peace.

We have consistently affirmed our identity as political fighters throughout our history of resistance and during our time in prison. As we stated on December 3, 2012, in our greeting sent to the international meeting on the political solution “Peoples Building Peace,” one passage reads:

Political prisoners have had to face, for years, the consequences of the conflict and of our ideological political commitment. For this reason, much of the penal code and penitentiary code serve the counterinsurgency role defined by the state. They are designed to punish dissidents or political opponents.

Camilo Torres Restrepo Political Prisoners Movement

We are imprisoned but we are not detained.

November 2018

Your emphasis on media asymmetry stood out to me. It’s something I’ve been reflecting on too: how narratives are weaponized not only to delegitimize resistance but to sanctify violence

I wrote something that lightly relates to some of the themes in your post, on dehumanization and the politics of personification. I would love it if you had a look!