Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice

Excerpts from book

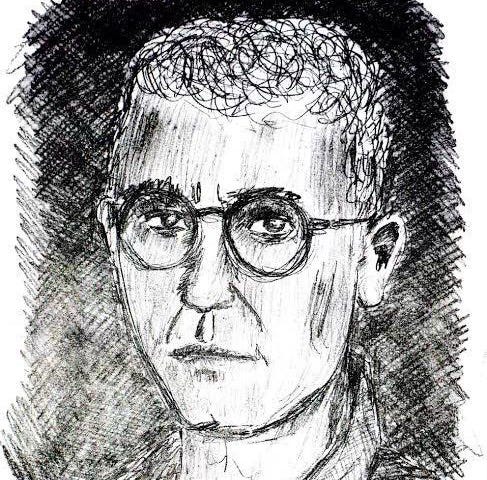

After World War II, the CIA wasn’t the only one doing research on counterinsurgency. Following the publication of The Pacification of Algeria in 1963, David Galula published Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice. Galula grew up in Tunisia and Morocco, later becoming a major and captain of the French Army during the Algerian Revolution (Marlowe, 2010). His wealth of knowledge of insurgency and counterinsurgency spanned from China’s Revolutionary War, Vietnam War, and the Greek Civil War, but his direct experience in Algeria commanding the 3rd Company of the 45th Colonial Infantry Battalion gave him the opportunity to apply and further theorize counterinsurgency.

In Marlowe’s intellectual biography, one learns that when Galula arrived in Algeria as a junior officer, he was directly involved in putting into practice the counterinsurgency concepts developed by French theorist-practitioners such as Charles Lacheroy and Roger Trinquier. However, his career took a turn when US General Edward Lansdale, an early supporter of Galula’s work, brought him to the United States, where Galula participated in the war college and think tank circuit during the initial surge of interest in counterinsurgency (COIN) theory in the early 1960s. With the additional backing of US General William Westmoreland, Galula secured a position at Harvard’s Center for International Affairs, where he authored his influential book on counterinsurgency.

Galula’s work resurfaced after 911 and War on Terror that ensued when it was cited by the US Military Field Manual (3-24) on Counterinsurgency led by General Patreaus in 2006. The recovery of Galula’s work sheds light on the colonial context from which counterinsurgency theory and praxis was established, particularly the role ideology plays in either strengthening or weakening an insurgency and the centrality of attaining the the support of a population, which the US military sought to imitate in Iraq and Afghanistan, albeit with much failure.

Galula wrote that an insurgency “cannot seriously embark on an insurgency unless” there’s a “well-grounded cause” the general population resonated with and finds legitimate (p. 8). Paraphrasing Clausewitz, Galula states that an “Insurgency is the pursuit of the policy of a party, inside a country, by every means” (p. 1). He also clarifies that an insurgency is not contingent upon the use of force since an insurgency can emerge long before force is needed. Before an insurgency engages in direct violence, particularly in the preparatory stages of organizing political education campaigns, counterinsurgent measures cannot be taken so easily, insofar as the former cannot be easily defined and located. While insurgency at this stage is an “imprecise, potential menace” (p. 3), it does not mean that nothing is to be done to stop it from expanding and becoming a revolutionary force that speaks to the people’s dreams of liberation. During the initial stages, according to Galula, counterinsurgency must “try to eliminate or alleviate the conditions propitious for an insurgency” (ibid).

While ideology is of key importance during the initial stages of an insurrection, the safety of the population, especially who will protect them from enemy forces, will greatly shape the population’s attitude toward the insurgency. There is no doubt that those leading a counterinsurgency also control the media and the information is disseminates. After all, ideological warfare is crucial to isolate an insurgent group from the population. Galula admits, however, that the most formidable asset an insurgency holds, albeit considered within the “field of intangibles”, is “the ideological power of a cause on which to” justify direct militant actions that will be based on strategies and tactics that will not only weaken the military position of counterinsurgency but also the political legitimacy upon which the State depends. Ultimately, an insurgency’s strategies and tactics are two-pronged: the insurgency weakens the enemy’s military, ideological, and political position and strengthens its own before, during, and after each encounter.

Echoing Mao Zedong’s work on revolutionary guerrilla warfare and protracted struggle, particularly on the importance of political clarity and military strategy, Galula notes that insurgents should always aim to weaken the counterinsurgent’s support received from the population, such as providing intelligence, military, or economic resources. The goal is therefore to strengthen and expand the population’s support.

“If the insurgent manages to dissociate the population from the counterinsurgent, to control it physically, to get its active support, he will win the war because, in the final analysis, the exercise of political power depends on the tacit or explicit agreement of the population or, at worst, on its submissiveness. Thus the battle for the population is a major characteristic of the revolutionary war” (p. 4).

In other words, a revolutionary war is always a political war, that is, a dispute over the State’s legitimacy to wield the power that it does, particularly over the monopoly of land and labor, which is fundamentally an economic question, which Fanon states at the beginning of The Wretched of the Earth: “For a colonized people the most essential value, because the most concrete, is first and foremost the land: the land which will bring them bread and, above all, dignity.” Therefore, it is indispensable that an insurgency’s political cause aligns with the people’s demands, which have been denied for far too long. If an insurgency fails to align its struggle with the people’s demands, it’s either due to a lack of political clarity and thus a weakened military position due to lack of population support, or it’s because counterinsurgency was able to effectively capture a population ideologically and physically, thereby isolating the insurgent “fish” from the people’s water, as Mao would put it. Both situations are dialectically constituted.

In conventional warfare between two relatively equal sides, on the other hand, military action suffices to fulfill the political aims. Clausewitz famous dictum points out that “war is nothing but the continuation of policy with other means” (69), illustrating that war is a necessary political instrument used when all other means have been exhausted. This understanding of warfare is what has shaped conventional wars, yet it falls flat when applied in revolutionary warfare. While the former employs positional warfare strategies and tactics as means to destroy the enemy’s military, the latter’s mobile guerrilla warfare depends on the political educational task of transforming a passive population into an active force that will be integrated into the strategies and tactics aimed at destroying the enemy not in one swift blow but through the protracted struggle of the people dispersed geographically in the enemy’s weakest military, political, and ideological positions.

Because of theorists such as Galula who learned from the theories, strategies, and tactics employed by multiple insurgencies, counterrevolutionary warfare’s counterinsurgent operations have imitated the former have emphasized political aims alongside military objectives. These become entwined in one another. Galula argued that “political action remains foremost throughout the war. It is not enough for the government to set political goals, to determine how much military force is applicable, to enter into alliances or to break them; politics becomes an active instrument of operation. And so intricate is the interplay between the political and the military actions that they cannot be tidily separated; on the contrary, every military move has to be weighed with regard to its political effects, and vice versa” (p. 5). Whereas an insurgency has a political and ideological advantage when the government’s military forces lack legitimacy, a counterinsurgency will be at a disadvantage when the government has lost legitimacy and an insurgency’s cause has already spread in the imagination and aspirations of the people.

Notes: If a community feels more protected by the insurgency, then counterinsurgency will be employed to create chaos to diminish support. These counterinsurgent efforts can revolve around economic sabotage of newly established autonomous regions in support of the insurgency. When this proves insufficient, the State or occupying power returns to conventional forms of warfare (systematic bombardment) that destroys life-sustaining infrastructure, as we have seen in Gaza. But to justify the State’s destruction requires ideological counterinsurgency to place blame on the victims (e.g., terrorists, human shields, children of darkness, Hamas started the war) through propaganda designed to convince the population of the lies narrated by the colonizer. The assassinations of leaders has also historically formed part of covert operations. The asymmetrical ideological and physical warfare waged against an insurgency thus constitutes the totality of counterinsurgency.